WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) ΓÇö Archaeologists in Virginia are uncovering one of colonial America's most lavish displays of opulence: An ornamental garden where a wealthy politician and enslaved gardeners grew exotic plants from around the world.

Such plots of land dotted BritainΓÇÖs colonies and served as status symbols for the elite. They were the 18th-century equivalent of buying a Lamborghini.

The garden in Williamsburg belonged to John Custis IV, a tobacco plantation owner who served in Virginia's colonial legislature. He is perhaps best known as the first father-in-law of Martha Washington. She married future U.S. President George Washington after CustisΓÇÖ son Daniel died.

Historians also have been intrigued by the elder CustisΓÇÖ botanical adventures, which were well-documented in letters and later in books. And yet this excavation is as much about the people who cultivated the land as it is about Custis.

ΓÇ£The garden may have been CustisΓÇÖ vision, but he wasnΓÇÖt the one doing the work,ΓÇ¥ said Jack Gary, executive director of archaeology at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum that now owns the property. ΓÇ£Everything we see in the ground thatΓÇÖs related to the garden is the work of enslaved gardeners, many of whom must have been very skilled.ΓÇ¥

Archaeologists have pulled up fence posts that were 3 feet (1 meter) thick and carved from red cedar. Gravel paths were uncovered, including a large central walkway. Stains in the soil show where plants grew in rows.

The dig also has unearthed a pierced coin that was typically worn as a good-luck charm by young African Americans. Another find is the shards of an earthenware chamber pot, which was a portable toilet, that likely was used by people who were enslaved.

Animals appear to have been intentionally buried under some fence posts. They included two chickens with their heads removed, as well as a single cowΓÇÖs foot. A snake without a skull was found in a shallow hole that had likely contained a plant.

ΓÇ£We have to wonder if weΓÇÖre seeing traditions that are non-European,ΓÇ¥ Gary said. ΓÇ£Are they West African traditions? We need to do more research. But itΓÇÖs features like those that make us continue to try and understand the enslaved people who were in this space.ΓÇ¥

The museum tells the story of VirginiaΓÇÖs colonial capital through interpreters and restored buildings on 300 acres (120 hectares), which include parts of the original city. Founded in 1926, the museum did not start telling , even though more than half of the 2,000 people who lived there were Black, the majority enslaved.

In recent years, the museum has to tell a more complete story, while trying to attract more Black visitors. It plans to reconstruct one of the and is restoring what is believed to be the countryΓÇÖs oldest .

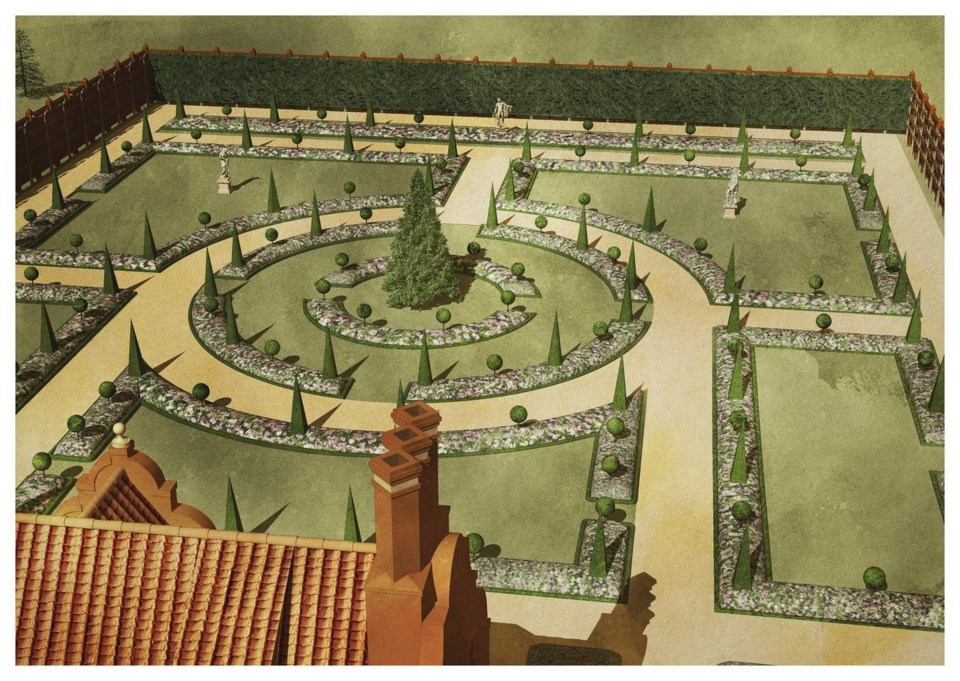

There also are plans to recreate CustisΓÇÖ Williamsburg home and garden, known then as Custis Square. Unlike some historic gardens, the restoration will be done without the benefit of surviving maps or diagrams, relying instead on what Gary described as the most detailed landscape archaeology effort in the museum's history.

The garden disappeared after Custis' death in 1749. But the dig has determined it was about two-thirds the size of a football field, while descriptions from the time reference lead statues of Greek gods and topiaries trimmed into balls and pyramids.

The gardenΓÇÖs legacy has lived on through CustisΓÇÖ correspondence with British botanist Peter Collinson, who traded plants with other horticulturalists around the globe. From 1734 to 1746, Custis and Collinson exchanged seeds and letters on merchant ships crossing the Atlantic.

The men possibly introduced new plants to their respective communities, said Eve Otmar, Colonial WilliamsburgΓÇÖs master of historic gardening. For instance, Custis is believed to have made one of WilliamsburgΓÇÖs earliest written mentions of growing tomatoes, known then as ΓÇ£apples of loveΓÇ¥ and native to Mexico and Central and South America.

Custis's gardeners also planted strawberries, pistachios and almonds, among 100 other imported plants. ItΓÇÖs not always clear from his letters which were successful in the Virginia climate. A recent pollen analysis of the soil indicates the past presence of stone fruits, such as peaches and cherries, which werenΓÇÖt a big surprise.

The garden existed at a time when European empires and slavery were still expanding. Botanical gardens often were used for discovering new cash crops that could enrich colonial powers.

But Custis' garden was primarily about showing off his own wealth. A study of the areaΓÇÖs topography placed his garden in direct view of WilliamsburgΓÇÖs only church house at the time. Everyone would have seen the garden's fence, but few were invited inside.

Custis delighted his guests with the likes of the crown imperial lily, which was native to the Middle East and parts of Asia, and boasted clusters of drooping, bell-shaped flowers.

ΓÇ£In the 18th century, those were unusual things,ΓÇ¥ Otmar said. ΓÇ£Only certain classes of people got to experience that. A wealthy person today ΓÇö they buy a Lamborghini.ΓÇ¥

The museum is still trying to learn more about the people who worked in the garden.

Crystal Castleberry, Colonial Williamsburg's public archaeologist, has met with descendants of the more than 200 people who were enslaved by the Custis family on his various plantations. But there is too little information in surviving documents to determine if an ancestor lived and worked at Custis Square.

Two people, named Cornelia and Beck, were listed as property with the Williamsburg estate after Daniel Custis died in 1757. But their names prompt only more questions about who they were and what happened to them.

ΓÇ£Are they related to one another?" Castleberry asked. "Do they fear being split up or sold? Or are they going to be reunited with loved ones on other properties?ΓÇ¥

Ben Finley, The Associated Press