ATCHISON, Kansas (AP) ΓÇö Among corporate AmericaΓÇÖs most persistent shareholder activists are 80 nuns in a monastery outside Kansas City.

Nestled amid rolling farmland, the Benedictine sisters of Mount St. Scholastica have taken on the likes of Google, Target and Citigroup ΓÇö calling on major companies to do everything from AI oversight to measuring pesticides to respecting the rights of Indigenous people.

ΓÇ£Some of these companies, they just really hate us,ΓÇ¥ said Sister Barbara McCracken, who leads the nunsΓÇÖ corporate responsibility program. ΓÇ£Because weΓÇÖre small, weΓÇÖre just like a little fly in the ointment trying to irritate them.ΓÇ¥

At a time when activist investing has become , these nuns are no strangers to making a statement. Recently they went viral for denouncing the of Kansas City Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker at the nearby college they cofounded.

When Butker suggested the women graduates of would most cherish their roles as wives and mothers, the nuns ΓÇô who are noticeably neither wives nor mothers ΓÇô expressed concern with ΓÇ£the assertion that being a homemaker is the highest calling for a woman.ΓÇ¥

After all, womenΓÇÖs education has been a mainstay of their community, which founded dozens of schools. Many of the sisters have doctorates. Most have worked professional jobs ΓÇô their ranks include a physician, a canon lawyer and a concert violinist ΓÇô and they have always shared what they earned.

They invest what little they have in corporations that match their religious ideals, but also keep a bit in some that donΓÇÖt, so they can push those companies to change policies they view as harmful.

This past spring and summer, when many companies gathered for annual meetings with their shareholders, the nuns proposed a string of resolutions based on stock they own, some in amounts as little as $2,000.

The sisters asked Chevron to assess its human rights policies, and for Amazon to publish its lobbying expenditures. They urged Netflix to implement a more detailed code of ethics to ensure non-discrimination and diversity on its board. They proposed that several pharmaceutical companies reconsider patent practices that could hike drug prices.

Up until the 1990s, the nuns had few investments. That changed as they began to set aside money to care for elderly sisters as the community aged.

ΓÇ£We decided it was really important to do it in a responsible way,ΓÇ¥ said Sister Rose Marie Stallbaumer, who was the communityΓÇÖs treasurer for years. ΓÇ£We wanted to be sure that we werenΓÇÖt just collecting money to help ourselves at the detriment of others.ΓÇ¥

Faith-based shareholder activism is often traced to the early 1970s, when religious groups put forth resolutions for American companies to withdraw from South Africa over apartheid.

In 2004, the Mount St. Scholastica sisters joined the Benedictine Coalition for Responsible Investment, an umbrella group run by Sister Susan Mika, a nun based at a Texas monastery who has been working in the field since the 1980s.

The Benedictine Coalition works closely with the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility, which acts as a clearinghouse for shareholder resolutions, coordinating with faith-based groups ΓÇô including dozens of Catholic orders ΓÇô to leverage assets and file on social justice-oriented topics.

The Benedictines have played a key role at ICCR for years, said Tim Smith, a senior policy advisor for the center. It can be discouraging work, where the needle only moves slightly each year, but he said the sisters ΓÇ£have the endurance of long-distance runners.ΓÇ¥

The resolutions rarely pass, and even if they do, theyΓÇÖre usually non-binding. But theyΓÇÖre still an educational tool and a means to raise awareness inside a corporation. The Benedictine sisters have watched over the years as support for some of their resolutions has gone from low single digits to 30% or even a majority.

Gradually environmental causes and human rights concerns have swayed some shareholders, even as a foments against investments involving ESG (environmental, social and governance concerns).

ΓÇ£We donΓÇÖt give up,ΓÇ¥ Mika said. ΓÇ£We just keep persevering and raising the issues.ΓÇ¥

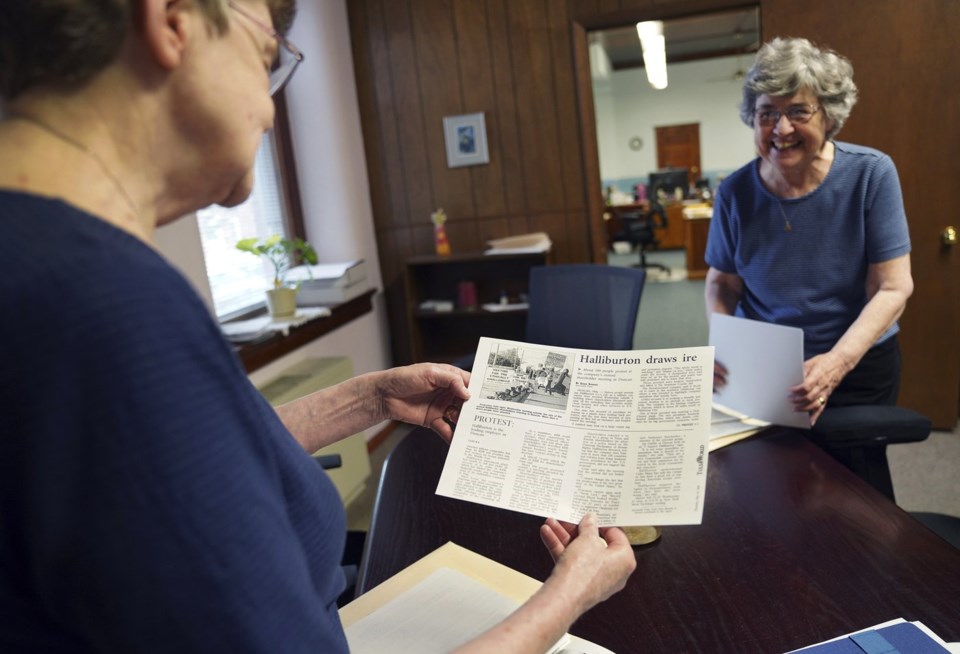

ItΓÇÖs a form of protest, which comes naturally to McCracken, the longtime peace activist who submits the Kansas nunsΓÇÖ resolutions.

ΓÇ£ThereΓÇÖs not a protest she wouldnΓÇÖt go to,ΓÇ¥ said Sister Anne Shepard, who rattled off McCrackenΓÇÖs past involving anti-war, anti-racism, union-backing demonstrations.

McCracken, who entered the Benedictine community in 1961 and later spent a decade at a , calls herself the ΓÇ£odd extrovertΓÇ¥ in monastic life, who ΓÇ£hates to miss a party.ΓÇ¥

She and her sisters live by the rhythms of ancient monasticism, praying and chanting three times a day in their chapel, much as their order has done for 1,500 years.

They follow the Benedictine motto to ΓÇ£pray and work,ΓÇ¥ and together the sisters pool their salaries, retirement funds, inheritances and donations to support their ministries and investments.

At the core of much of what they do is the belief that the wealthy have too much, the poor have too little, and more should be shared for the benefit of everyone. Or as they say in Catholic parlance, for the common good.

ΓÇ£To me, itΓÇÖs a continuation of Catholic social teaching,ΓÇ¥ McCracken said of their activist investing.

Catholic social teaching defies tidy American political categories. ItΓÇÖs against abortion and the death penalty, for the poor and the immigrant. Pope Francis has renewed his churchΓÇÖs call to care for the Earth through his landmark environmental writings.

The Mount St. Scholastica sisters have long had an ecological focus: Their collegeΓÇÖs alumni include , the late Kenyan environmental activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner.

One of their top concerns these days is climate change, a frequent target of their shareholder resolutions. To do their part, they use their 53 acres of land for compost, solar panels, community gardens and 18 beehives that produced 800 pounds of honey last year.

Their activism has often led to criticisms that theyΓÇÖre too liberal, that theyΓÇÖre all Democrats.

One reason for that perception is their community is ΓÇ£not at the forefront of opposition to abortion,ΓÇ¥ McCracken said, though sheΓÇÖs clear they follow church teaching on the matter. But with so many Catholic groups leading the anti-abortion movement, they find other causes to champion.

The also prompted plenty of angry calls and emails to the monastery. And it particularly stung because the sisters are devoted Chiefs fans, known to file into chapel decked out in red and gold on game day.

Sister Mary Elizabeth Schweiger, the monasteryΓÇÖs prioress, wrote the statementΓÇÖs first draft.

ΓÇ£We reject a narrow definition of what it means to be Catholic,ΓÇ¥ it read, in response to ButkerΓÇÖs denigration of ΓÇ£the tyranny of diversity, equity and inclusion.ΓÇ¥

ΓÇ£It came from a very basic understanding of who we are and the values that we hold true,ΓÇ¥ Schweiger said later in her office. ΓÇ£We just thought that voice had to be heard because we believe very much in being inclusive.ΓÇ¥

For being bold about what they believe, and wading into controversial subjects, they have both lost and gained supporters for decades.

ΓÇ£Living according to the gospel ... itΓÇÖs going to intersect with politics and economics both,ΓÇ¥ McCracken said. ΓÇ£ItΓÇÖs just the nature of being an active citizen.ΓÇ¥

At nearly 85, McCracken canΓÇÖt be as active as she once was. But shareholder activism provides her with ΓÇ£a sit-down job when you canΓÇÖt go to the streets.ΓÇ¥

The sisters of Mount St. Scholastica donΓÇÖt retire, not really.

ΓÇ£We donΓÇÖt use that word,ΓÇ¥ McCracken said. ΓÇ£If we still have enough wits about us, we just keep going, you know?ΓÇ¥

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the APΓÇÖs with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Tiffany Stanley, The Associated Press