As Bob Taylor would later tell his daughter, his first call working for Richmond Fire-Rescue was responding to a fatal, multi-vehicle crash on Westminster Highway.

It was back in the 1970s, and when Taylor got on scene the officer in charge told him to go into the bushes to retrieve one victim’s severed head. New on the job, Taylor put on gloves, readied a plastic bag and moved into the brush to collect it.

Responding to graphic, traumatic calls is part of every firefighter’s job. It takes a toll on anyone, and what makes it worse, said Fire Chief Tim Wilkinson, is the sense of helplessness that despite your best efforts, people still die.

But even though firefighting is a hard job, Taylor was good at it. He was brave, caring and “tough as nails,” his daughter Christy Judd told the Richmond News. He rose through the ranks to become a captain, and in 2004 was named Firefighter of the Year before being named Fire Captain and Crew of the Year in 2005.

“Being a firefighter was in my dad’s blood,” Judd said. “Saving people’s lives was what fed his soul.”

On Oct. 14, Taylor died by suicide. He was 65 and had been retired for about a decade.

He was dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder, his family said. It’s a mental illness that can develop following a traumatic event. It’s characterized by intrusive memories, flashbacks or nightmares and agitation or a feeling of numbness or detachment.

“He said he couldn’t stop the pounding in his brain,” Judd said.

It’s a disorder that’s more prevalent in first responders than the general population. One German study found that nearly 20 per cent of surveyed firefighters presented with symptoms of PTSD. A that surveyed about 6,000 public safety personnel found that 45.5 per cent of them screened positive for “clinically significant symptom clusters consistent with one or more mental disorders."

A U.S. says that in any given year a department is four times more likely to experience a member dying by suicide than being killed in the line of duty.

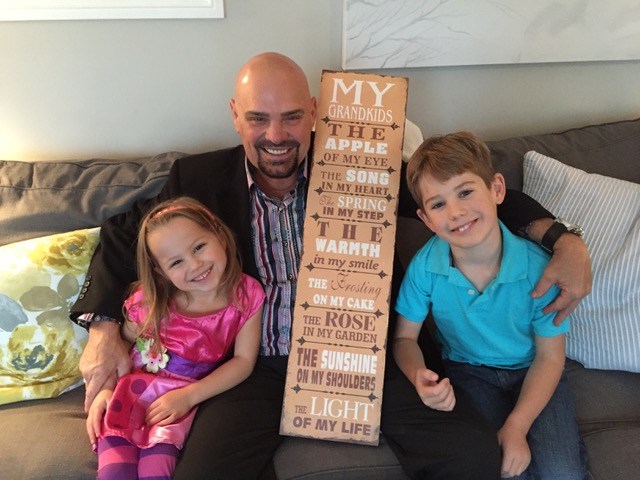

Judd remembers her dad as “larger than life,” someone prone to doing random acts of kindness for strangers, like leaving a cold case of beer on his neighbour’s steps when he moved into his apartment.

Don Taylor, Bob’s younger brother, also remembers him as someone with a “passionate character.” The two were close, playing sports together and growing up on Francis Road in Richmond.

“I had it pretty easy growing up, because I was Bob Taylor’s little brother,” he said.

Taylor’s death is making the department’s current focus on mental health all the more pertinent and calling into question whether more can be done to help retirees.

Richmond Fire-Rescue focusing on mental health

Although firefighters have always been exposed to gruesome and disturbing situations, only recently has the profession begun to realize the immense mental toll those take. Several high-ranking members of Richmond’s fire department have noted the 180-degree shift the profession has made in the last decade or so, going from a place where a stoic attitude was prized to one where mental health is taken very seriously.

The Richmond department has implemented Critical Incident Stress Management sessions, where firefighters who go out on a traumatic call are taken aside and debriefed on their reactions afterwards. The department has also implemented mandatory mental health training courses like Resilient Minds and the Road to Mental Readiness.

“Basically, a person has a capacity to take on trauma. And we’re all a little bit different. We’ve taken on a bit more or a bit less. But once you’re full, you’re full. You can’t take any more,” Wilkinson said.

He hopes the department’s education efforts give them the ability to process and “shed” that trauma.

Jim Dickson, another Richmond firefighter, is a Resilient Minds trainer who delivers the program to his peers.

In the workshops, firefighters role play scenarios. Some involve responding to calls where a member of the public is in crisis. Other times, it’s a colleague.

“You definitely get a sense from the room that it’s not an easy topic, even though we’re just role playing. They’re not easy conversations -- but they’re necessary,” Dickson said.

Vancouver Fire-Rescue also implemented the program, and 70 per cent of members who went through it said they use the techniques regularly at work and at home.

Dickson remembers the very first Resilient Minds class he ran was on the Monday after Bryan Kongus’ funeral, a Richmond firefighter who died as a result of work-related PTSD. Needless to say, there was buy-in from members to participate.

Although, today, it is strongly impressed on new recruits that Richmond Fire-Rescue takes mental health seriously, that wasn’t always the case.

Wilkinson, Dickson and Cory Parker, president of Richmond’s firefighter union, are all more than 25 years into their firefighting career. They all said when they started, things were much different.

“The follow-up 20 years ago was the captain saying ‘you ok?’,” Parker said.

“Well, a number of years back you would have a couple of drinks. So basically, you dull the feelings,” Wilkinson added.

Judd said her dad came from a generation of firefighters that formed a sort of “old boys club,” where you didn’t talk about mental health struggles. As a result, he didn’t have the tools to deal with his post-traumatic stress disorder.

Should more support be available to retirees?

Parker believes there’s still catching up to do, for a profession that for so long prided itself on toughness.

While active members have workplace benefits and coverage for things like psychologist appointments, Parker is worried about retirees slipping through the cracks.

Judd said she’d like to see more outreach to retirees—perhaps information packages delivered to their door detailing the supports available. Don, Taylor’s brother, agreed.

Steve Fraser, with Vancouver Fire-Rescue, said the BC Professional Fire Fighters Association has recently opened up mental health retreats to retirees. They’re courses involving group work and sessions with mental health professionals that last several days.

But besides that, he said he’s not sure what to tell retirees other than to seek help through community supports like family doctors and private counsellors.

“That’s something that I struggle with often, what to do with our retired members. Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of answers,” he said.

Dr. Lynn Alder, a clinical psychologist at the University of British Columbia, said that for most people, symptoms of acute stress or PTSD will fade within three months of the event. But for the minority of people whose symptoms persist past six months, they’re unlikely to go away without treatment.

“Even after retirement, these people are at risk for PTSD,” she said, adding that sometimes being less busy with work can make symptoms more pronounced. “[Developing PTSD is] more likely the more of these traumatic events they experience.”

Earlier this year, amendments were made to worker’s compensation legislation so that mental disorders that occur in workers who are first responders are automatically assumed to be caused by exposure to traumatic incidents at work. Before, the onus was on the first responder and their family to prove that was the case.

But it’s unclear what these changes might mean for a first responder like Taylor who was retired.

Conrad Margolis, a Richmond lawyer who deals with WorkSafeBC and Workers’ Compensation Board claims, says getting compensation for work-related psychological conditions is often still a struggle for families.

The new legislation came into effect on May 17, 2018 and only applies to WCB decisions made after that date. Though Taylor died in October, he stopped working long before.

“The family probably does have an uphill battle here,” he said.

�ճ����Richmond News asked WorkSafeBC what the new legislation might mean for a retiree, but a spokersperson for the agency said it was a complex issue that could only be answered by knowing the specifics of a person’s case.

Deaths illustrate the importance of focusing on mental health

Wilkinson said he doesn’t want firefighters like Taylor or Kongus to be made into martyrs. But, at the same time, their deaths reinforce how necessary a proactive approach to mental health is.

He wants every member to feel comfortable reaching out for help.

“You’re an action-oriented person. We hired you to be that, so take action. If you’re having a struggle with your mental health, that’s not a bad thing. Go to a psychologist, go to a counsellor. Delve into it, and take your life into your own control.”

Judd thinks the department’s current focus on mental health is “the best news possible.”

“It’s hopefully going to save a life. It’s going to save a family losing their loved one."